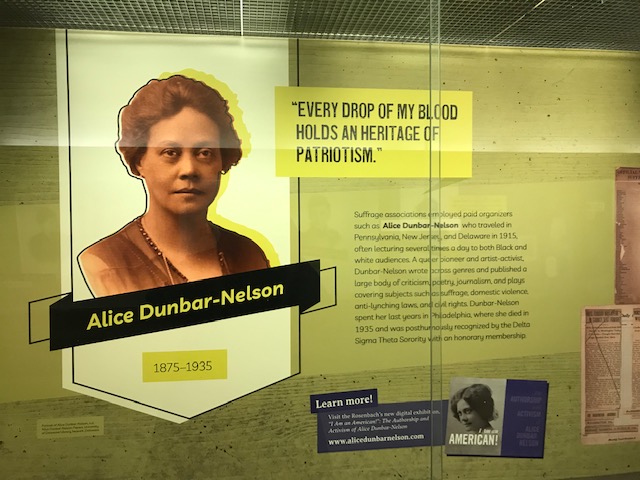

African American suffragists like Alice Dunbar-Nelson fought for more than votes for women.

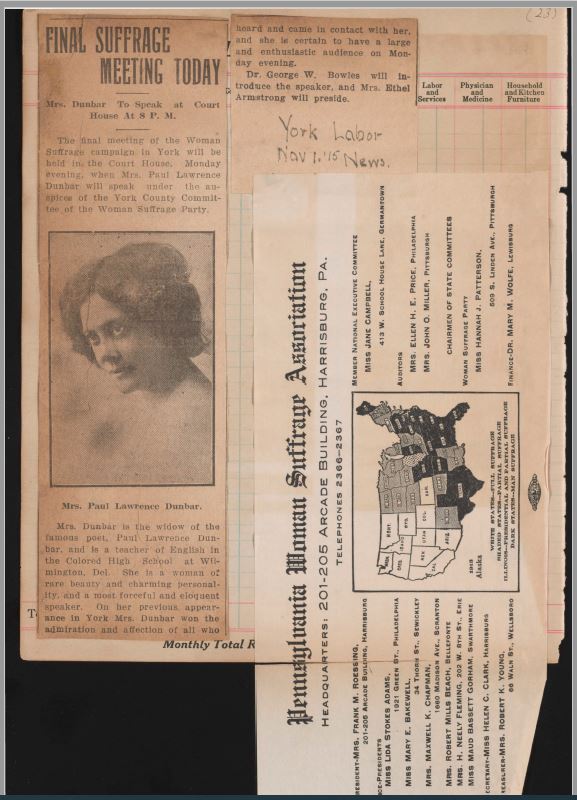

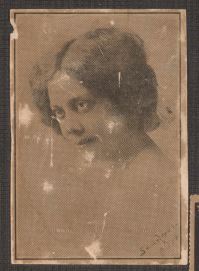

Photo of Alice Dunbar-Nelson from her scrapbook cover

White suffragists often appealed to “fairness” in seeking the right to vote. But that wasn’t enough for many African American suffragists. When Alice Dunbar-Nelson campaigned for votes for women in 1915, she explained to Black men that Black women’s voting would strengthen the Black community.

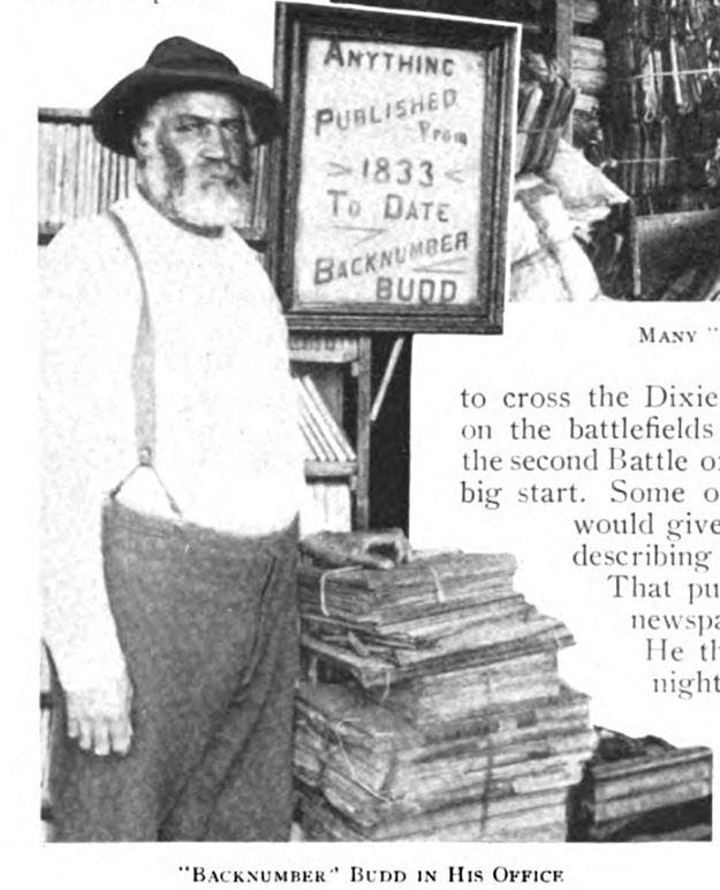

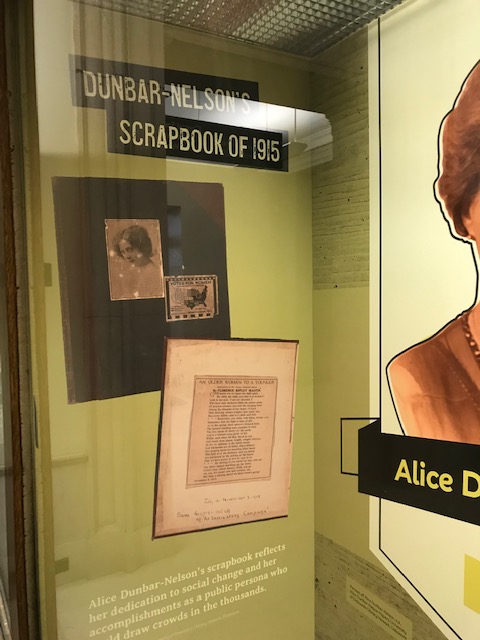

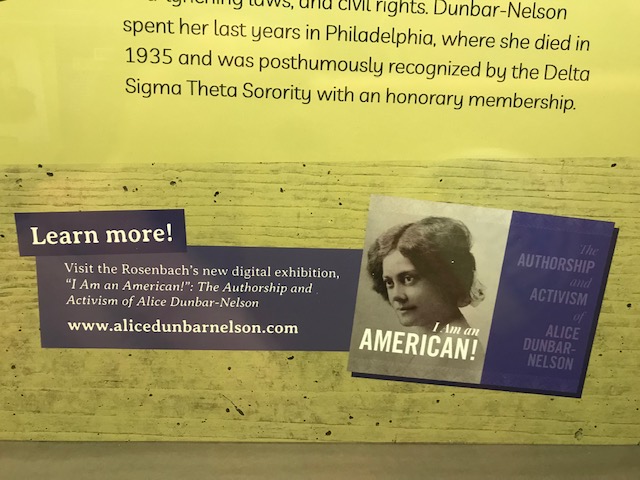

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson was a writer, teacher, poet, playwright, accomplished public speaker, and an anti-lynching activist of enormous energy and vision. But her suffrage work is missing from white-centered women’s rights histories. The scrapbook she kept documenting her speaking tour for a Pennsylvania suffrage campaign in 1915, however, reveals her role in winning women the right to vote. Newspapers wrote down parts of her speeches, and although she did not save full copies of her talks, without the scrapbook record she created, these articles would have been lost, as most have been saved nowhere else.

She took a break from her position as a English teacher at all-Black Howard High

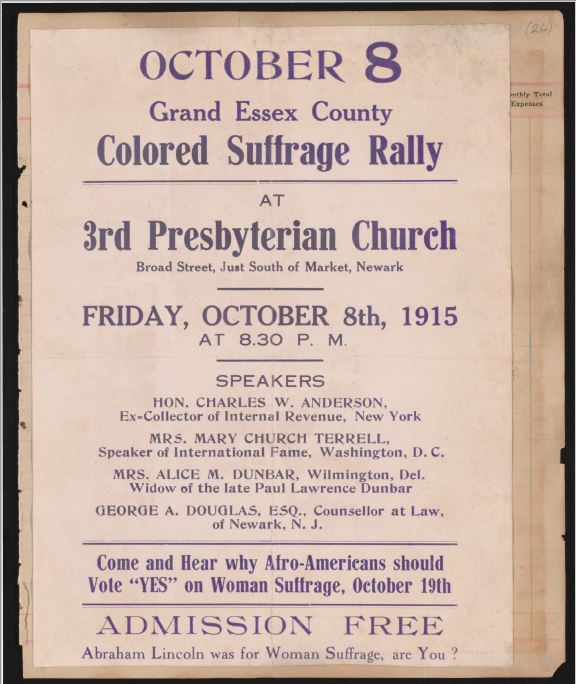

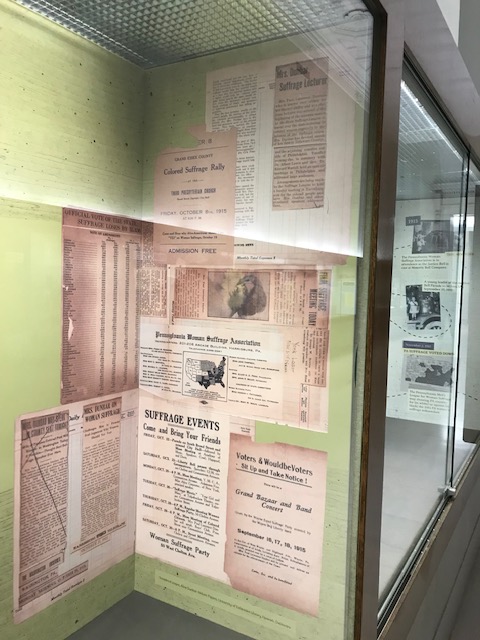

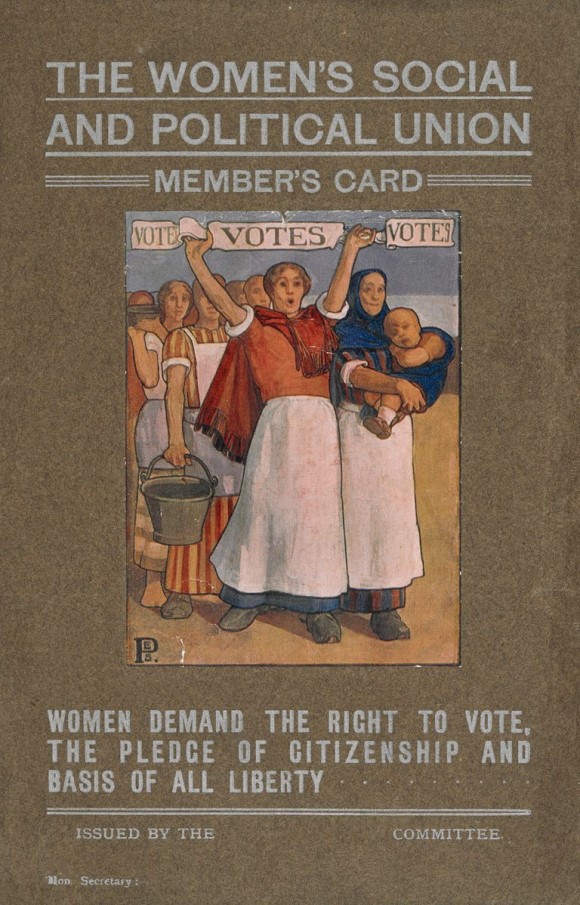

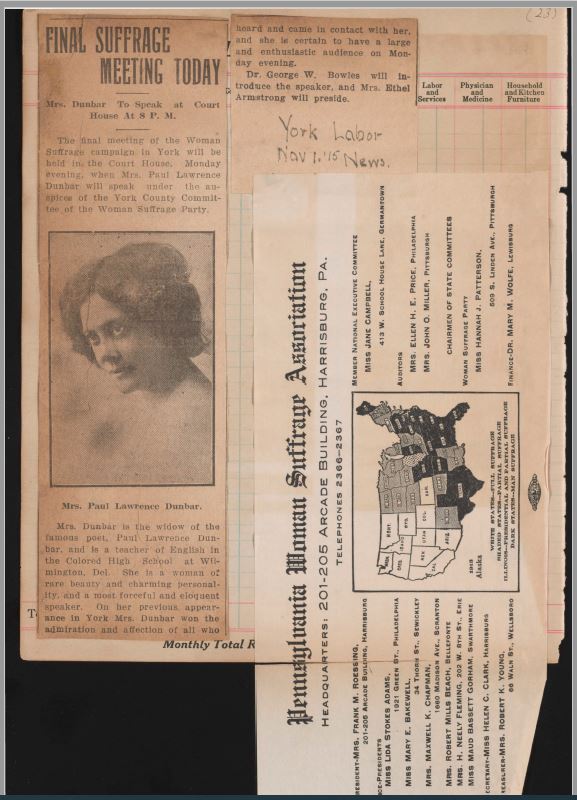

Flyer for African American women’s suffrage rally. Dunbar-Nelson’s friend Mary Church Terrell was also on the speaking circuit.

School in Wilmington, Delaware to participate in the suffrage campaign in fall 1915, working with the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s Speaker Bureau. But she wasn’t just any Bureau speaker bringing the (white) suffrage message into Black neighborhoods. Her speeches on what Black women’s votes could do for the Black community show she thought of suffrage more broadly. Her talks reached mixed-race, mixed gender, and all Black audiences. Of course only men were allowed to weigh in on whether women could ever cast a ballot, so she had to persuade men to support women’s right to vote.

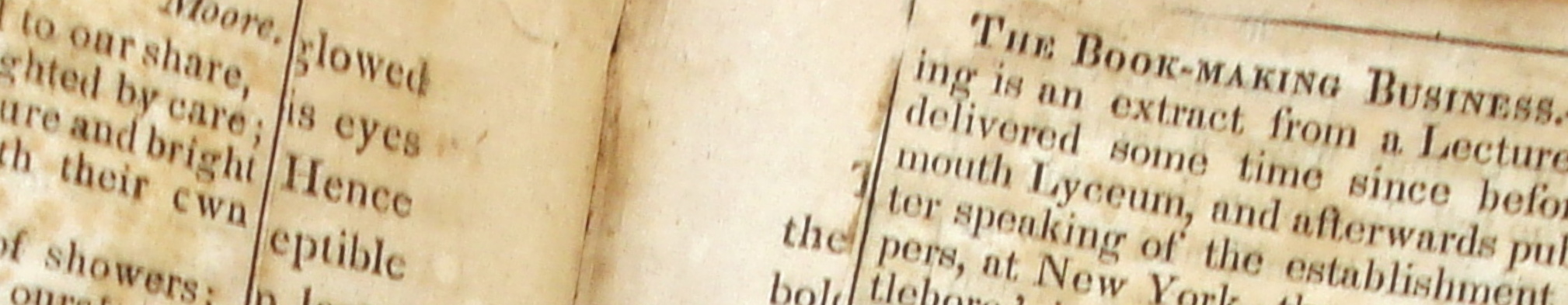

The map was classic suffrage swag, showing the growth of women’s right to vote. Like many scrapbook makers, Dunbar-Nelson reused an old book or ledger. Hers was a household accounts book, seemingly never used. When scrapbook makers pasted over other books, they demonstrated that they valued one text over the other: in this case, suffrage self-documentation (and the housekeeping of the community) over close attention to individual housekeeping.

Although white suffragists often spoke or wrote as though women were not working for wages, Alice Dunbar-Nelson explained repeatedly that Black women’s work outside the home benefited the Black community as a whole. She argued to a Black audience, “Our women have literally built up [our] race in domestic service, which keeps them out of their home all day long; that means that the majority of our women are out of their homes every day helping the men to accumulate [resources]. If we are good enough to help in all this, it looks as if we are good enough to cast a vote.” When anti-suffragists claimed that politics was too “dirty” for women, Dunbar-Nelson responded, “Politics is the only dirt we don’t get into at present.”

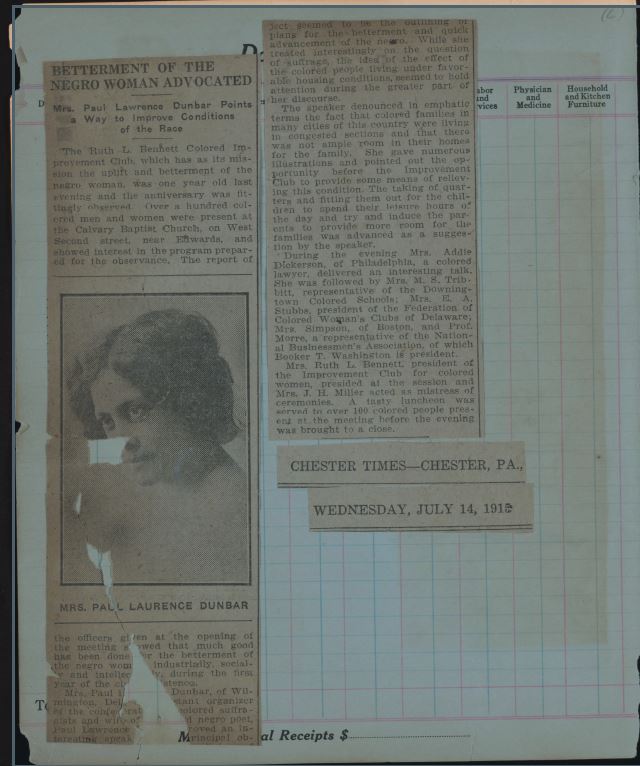

Like today’s Black Lives Matter activists who focus on housing inequities as well as

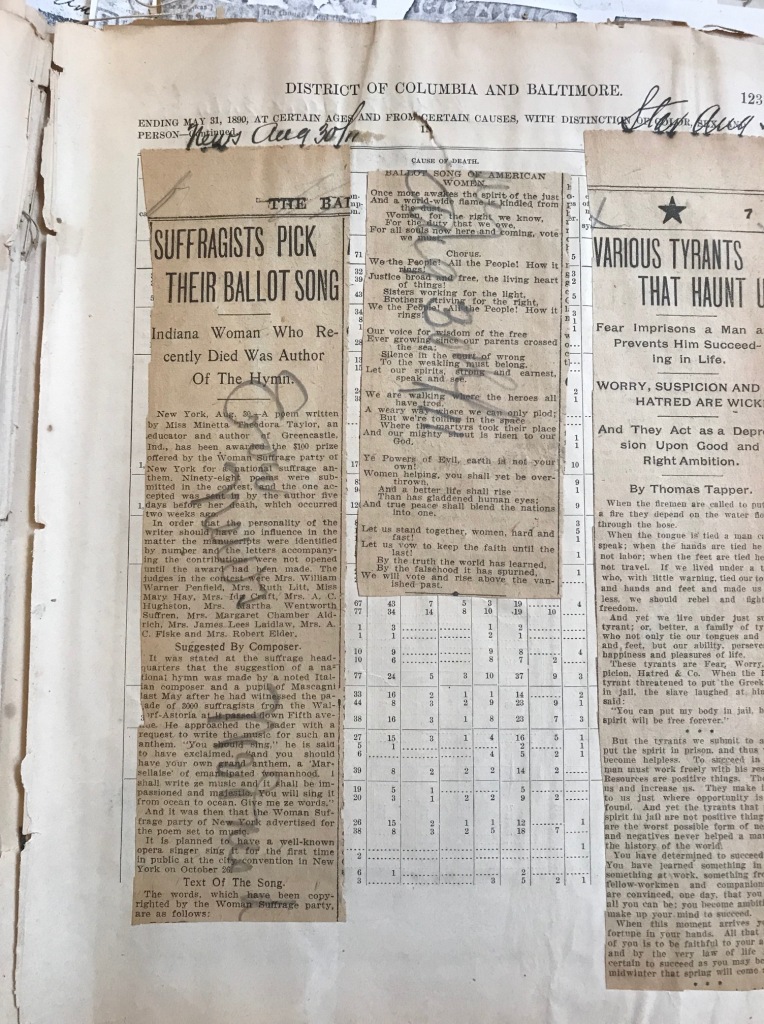

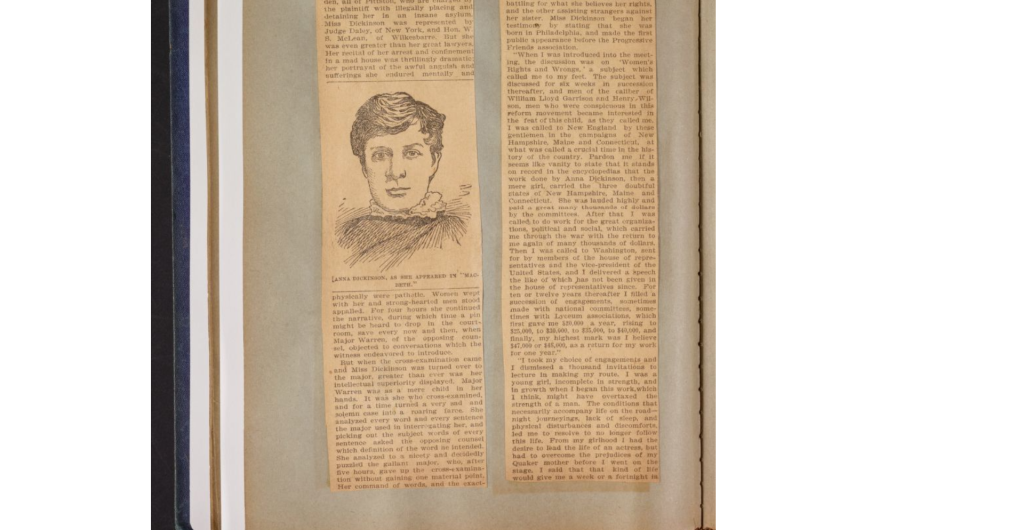

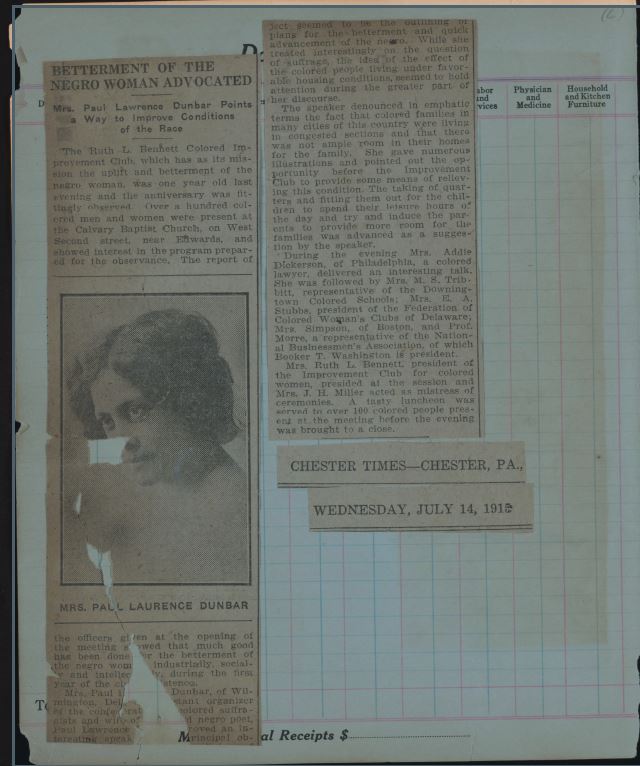

Clipping about Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s talk to a Black women’s suffrage organization.

police violence, Alice Dunbar-Nelson spoke out on how winning the vote would make Black women more effective advocates for better housing. She argued that voters could address the needs of Black families coming north in the Great Migration, who lived in overcrowded ghetto housing. In one talk to a Black women’s group, she “denounced in emphatic terms the fact that colored families in many cities of this country were living in congested sections and that there was not ample room in their homes for the family,” her scrapbook clipping records. Suffrage was not just about the vote itself, but what African American women could change with the vote.

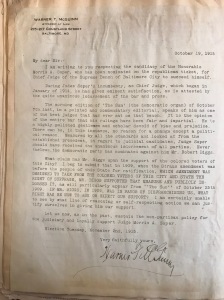

The only item in her scrapbook not directly related to the suffrage campaign concerns her testimony against the film The Birth of a Nation in a court hearing. The popular film showed African Americans as violent beasts that the KKK had to restrain by lynching. She was already an anti-lynching crusader and an early member of the NAACP. Pasting this item into her suffrage scrapbook, Dunbar-Nelson made clear that Black women’s vote and advocacy should be used to combat racism.

And so, when women finally won the vote, Dunbar-Nelson was more than ready for it. She organized Black women to cast their votes effectively and not be limited by party loyalty. She first worked arduously for Republicans, which was then the more progressive party. When white Republican politicians failed to support an anti-lynching measure, she switched her party affiliation to Democratic, and worked for Al Smith.

Black women have continued to be leaders in progressive, anti-racist politics, and now even run for Vice President.

You can read Alice Dunbar Nelson’s complete suffrage scrapbook, “”July 12 – November 3, 1915. Some Records, not all of `An Interesting Campaign'” online at the University of Delaware Special Collections.

I’ve written briefly about Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s suffrage scrapbook previously here. My longer article about her scrapbook, “Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson’s Suffrage Work: The View from Her Scrapbook,” is in Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers, special issue: Recovering Alice Dunbar-Nelson for the Twenty-First Century, Volume 33, No. 2, 2016. It’s better for Legacy if you access it from an academic library, but if you can’t, you can get it here.

As we get closer to the November 3, 2020 election, I will frequently post items about voting from my research on old scrapbooks here on the Scrapbook History website. Scrapbook makers collected many items from the newspapers that were deeply significant to them about why people, especially women of all groups and Black people, fought for the right to vote, how they used their vote, how they fought voter suppression, and sometimes how they honored those who fought and voted. Their scrapbooks were tools in their struggles.

As we get closer to the November 3, 2020 election, I will frequently post items about voting from my research on old scrapbooks here on the Scrapbook History website. Scrapbook makers collected many items from the newspapers that were deeply significant to them about why people, especially women of all groups and Black people, fought for the right to vote, how they used their vote, how they fought voter suppression, and sometimes how they honored those who fought and voted. Their scrapbooks were tools in their struggles.