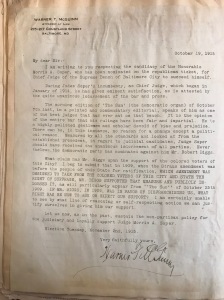

Warner T. McGuinn, in an article celebrating his victory against a segregation ordinance, saved in his own scrapbook.

African Americans in law and politics have known to keep a close eye on the courts, as the scrapbook of Warner Thornton McGuinn, an African American lawyer, shows. In an era when newspapers rarely published their indexes and libraries did not always save dailies, scrapbooks stored up evidence of politicians’ past activities and positions and were a tool African Americans in law and politics used to keep a close eye on the courts. McGuinn was an 1887 Yale Law School graduate who moved to Baltimore in 1891, and began his scrapbook at the turn of the century. His scrapbook tracks his law career and the public offices he held. He worked against a Maryland law mandating racial segregation in housing. He clipped items about Black life in Baltimore, such as the founding of a Negro theater company in 1916, and on issues in other cities, including an article on a textbook controversy in New Orleans – a white writer objected because it

Clipping on Black theater company in Baltimore.

assigned students to write an essay on Booker T. Washington. When newspapers wrote about him, he saved the article, such as when he gave the main oration at a local memorial gathering for Frederick Douglass in 1905.

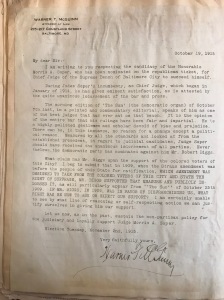

McGuinn collected news items about the suppression of Black voting in Maryland. His clippings from the white press were ammunition against politicians who had supported any of the three early 20th-century bills aimed at stripping the vote from African Americans in Maryland. He could bring them out as evidence of a politician’s earlier actions. In a copy — very possibly a facsimile created to circulate — of his own typed 1915 letter to the Baltimore Sun, complaining of their endorsement of Robert Biggs for Chief Judge in Baltimore, which he pasted into his scrapbook, he refers to an article he’d saved from six years earlier. Biggs had supported the Straus Amendment, “WHICH AMENDMENT WAS DESIGNED TO TAKE FROM COLORED VOTERS IN THIS CITY

Warner McGuinn’s letter pointing out that a nominated Chief Judge had supported suppression of the Black vote.

AND STATE THE RIGHT OF SUFFRAGE,” as is evident from a 1909 newspaper clipping from the Baltimore Sun. “IF MR. BIGGS, IN 1909, WAS IN FAVOR OF DISFRANCHISING US, WHAT RIGHT HAS HE NOW TO ASK OR EXPECT OUR SUPPORT?” McGuinn continues in all caps. He concludes with a plea for a nonpartisan judiciary, and support for his candidate, Morris Soper. It was important to stop the appointment of judges who opposed Black people voting.

Warner McGuinn connected Black and women’s disenfranchisement, and fought for women’s suffrage, speaking out for it and collecting pro-suffrage songs and poems in his scrapbook.

Item on women’s suffrage – who knew that there were ballot songs?

Like many other scrapbook makers, he glued his materials onto the pages of an old book. The book’s title is covered over, but columns of statistics peep out from behind his pasted down clippings. He did not use a Mark Twain self-pasting scrapbook, though Mark Twain fans remember Warner McGuinn because Twain helped pay for a portion of McGuinn’s time at Yale Law School. McGuinn was a law student and president of the Law School’s Kent Club, which hosted talks and debates on social and political questions. When the club invited Mark Twain to speak in 1885, McGuinn greatly impressed Twain when he showed him around the campus.

McGuinn was working his way through law school – first as a waiter, and then in a law

Label inside the Mark Twain Self-Pasting Scrap-Book gives instructions for use.

office — when Twain offered to pay for the final year and a half of his studies. Twain’s action has become part of the long history of exaggerating white benevolence. William Dean Howells says, by way of explaining that his friend was a “desouthernized Southerner” that he paid “the way of a negro student through Yale.” A handwritten note on McGuinn’s scrapbook in the Yale Library collection says it was made by “the black put threw Yale Law School by Mark Twain.” Twain’s largesse is thus exaggerated, and McGuinn’s status lowered.

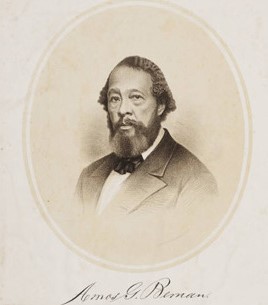

Thurgood Marshall, mentored by McGuinn.

But when McGuinn reached out to help others, he left a mark, and his decades of activism stretched farther into the future. He mentored the groundbreaking civil rights attorney and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, who established the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Justice Marshall continued McGuinn’s work of fighting voter suppression. One of its early cases established the right of Black voters in Texas to vote in Democratic primaries. Thurgood Marshall said Warner T. McGuinn should have been a judge himself.

Warner T. McGuinn’s scrapbooks are in the Yale Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection (MS 1258). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

Amos Beman clipped articles about African Americans who organized against voting restrictions. One eloquent piece in the weekly Colored American pressed for continued agitation, and called for a meeting in August 1841. Signed by Henry Highland Garnet and others, it roused readers to keep up the struggle in the face of the NY state legislature’s failure to act in the previous session:

Amos Beman clipped articles about African Americans who organized against voting restrictions. One eloquent piece in the weekly Colored American pressed for continued agitation, and called for a meeting in August 1841. Signed by Henry Highland Garnet and others, it roused readers to keep up the struggle in the face of the NY state legislature’s failure to act in the previous session:

nd editor Jeannette Leonard Gilder kept scrapbooks and wrote about her NJ life in her memoir, The Tom-Boy at Work. Isn’t it time for your historical society to bring out its scrapbooks?

nd editor Jeannette Leonard Gilder kept scrapbooks and wrote about her NJ life in her memoir, The Tom-Boy at Work. Isn’t it time for your historical society to bring out its scrapbooks?

s rare, riveting photograph of Harriet Tubman, probably taken around 1911 at her home in Auburn, NY, was in one of the scrapbooks kept by Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller. They were ardent suffragists, and the daughter and granddaughter of abolitionist Gerrit Smith. You can see

s rare, riveting photograph of Harriet Tubman, probably taken around 1911 at her home in Auburn, NY, was in one of the scrapbooks kept by Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller. They were ardent suffragists, and the daughter and granddaughter of abolitionist Gerrit Smith. You can see